Weak Backwardation?

- bkkelly6

- Dec 6, 2020

- 5 min read

Author: Brynne Kelly (w/Lee Taylor technical levels)

The 2020 pandemic has ravaged the crude oil complex and led to severe under-utilization of capacity across the system. Prior to 2020, the petroleum complex had been riding a high of new infrastructure additions that unlocked supply bottlenecks. US oil production growth largely ignored price signals in anticipation of logistical constraints being eliminated (i.e. new pipelines, USGC export infrastructure) and a growing export market.

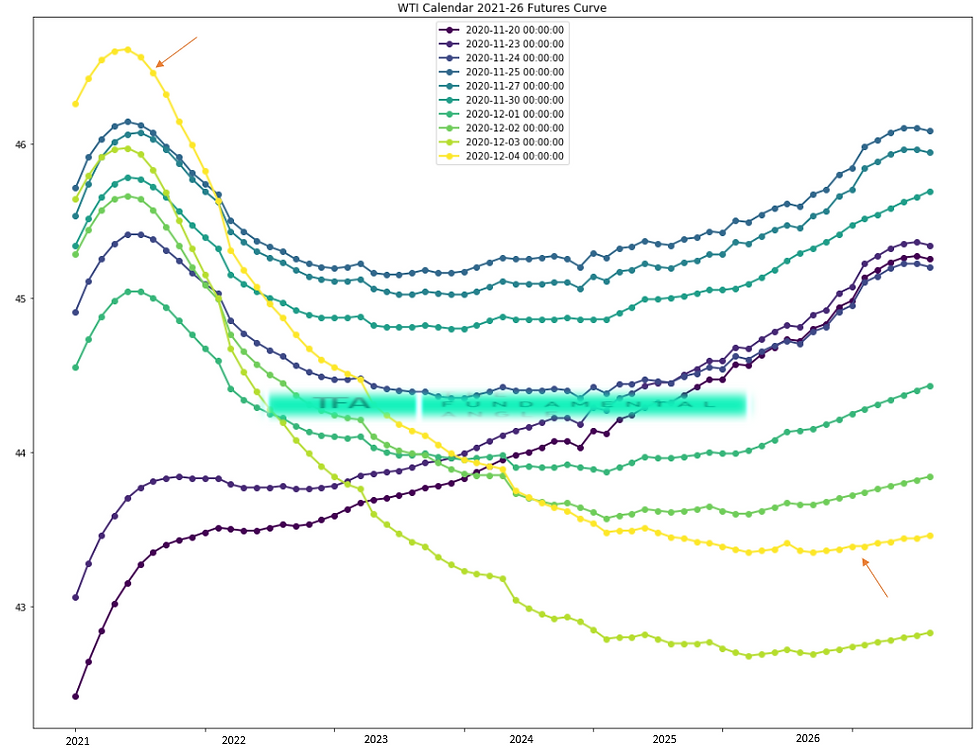

Against that backdrop of bearish fundamentals this year, the shift in the term structure of oil markets from contango to backwardation over the last 2 weeks is nothing short of amazing.

A few weeks back we wrote about the potential for oil markets to move into backwardation. We suggested that short-term supply constraints that arise as a result of production discipline will have a tough time filtering through to longer-dated prices, which seem to have fully-embraced the peak demand narrative.

Indeed this seemed to have played out in the days leading up to and after the OPEC meeting, the market structure flipped from contango to backwardation as the market embraced the OPEC+ outcome. You'll notice that the first 5 months of the WTI curve are still in contango. There is an interesting push/pull going on here between expected production increases from OPEC+ and short-term demand decreases due to the coronavirus as it appears the market expects short-term fundamentals to remain somewhat weak due to the pandemic.

How do we frame such backwardation in light of everything that has happened this year?

In conditions of certainty, it is argued that the net price of an exhaustible resource like crude oil will rise over time at the rate of interest (Hotelling’s theory). This implies that oil futures prices will not exhibit (weak) backwardation unless extraction costs rise by less than the interest rate. Of course this theory makes some big assumptions:

Events take place in an efficient market.

Factors that will affect the supply of the exhaustible resources, such as new discoveries and technology, are non-existent.

Obviously, markets rarely operate with certainty. Under uncertainty, ownership of oil reserves may be viewed as holding a call option whose exercise prices corresponds to the extraction cost. In that case, backwardation arises from the equilibrium trade-off between exercising the option (i.e. producing the oil) and keeping it alive (i.e. leaving the oil in the ground). If discounted futures prices were higher than the spot price and if extraction costs grew by no more than the interest rate, all producers would rationally choose to defer production. Therefore, weak backwardation is a necessary condition for current production. If the uncertainty about futures prices is substantial, strong backwardation may be required in order to induce current production, even if extraction costs rise at the rate of interest.

This brings us to the OPEC+ decision. Prior to their meeting (although maybe in anticipation of the meeting?) one-month calendar spreads began strengthening as seen in the 10-day calendar spread curve shift below.

This is a 'clever' market, one that reluctantly compensates storage holders to store oil at the extremes of oversupply via contango. Absent extreme conditions, calendar spreads revert towards weak backwardation. We think flat to weak backwardation is here to stay as the worst shocks to the market from the pandemic appear to be behind us. We now enter a period of 'show me' markets where futures prices are led by spot market fundamentals. This will continue unless storage capacity becomes overwhelmed.

What would help keep the overall crude oil curve in backwardation?

OPEC+ adherence to schedule

As long as OPEC demonstrates it is complying with their gradual production increases, the market will have more clarity regarding short term supply demand fundamentals than longer-term.

Decline in US shale production

A lackluster response by producers to increase production as prices increase.

Increased refinery runs

Absent runaway product builds, refiners will be the first to increase throughput if margins recover.

Its not hard to imagine these three tenets being drivers in keeping the overall crude oil curve in backwardation. However, looking at spare capacity, the picture isn't as clear, capacity overhangs are problematic. Spare capacity needs to absorbed or eliminated before markets can move higher.

IDLE CAPACITY

Over the last 5 years, US oil production growth largely ignored price signals in anticipation of logistical constraints being eliminated (i.e. new pipelines, USGC export infrastructure and a growing export market). The status quo was significantly disrupted in 2020 with the onset of the coronavirus pandemic. The hit to demand forced refiners offline which immediately backed crude oil up into the system and forced producers to shut-in as they were left with crushed margins and limited outlets for their product.

Suddenly, across the energy industry, there is idle capacity. As economic incentives shift the focus away from traditional fuel usage, idled capacity walks a fine line between serving future demand growth or becoming a stranded asset. The amount of money invested in US energy infrastructure over the last decade - which provided ample supply and low prices - is staggering. Increasingly, individual state mandates that deviate from federal mandates are creating price dislocations. In the past, large price spreads between regional markets have attracted infrastructure investments like pipelines to alleviate bottlenecks. In today's regulatory environment it seems less and less likely that price dislocations will have the same ability to attract capital investment in traditional energy sources. The market has been burned by the existing model one too many times. Under the umbrella of climate change the country seems almost giddy to abandon the current infrastructure in favor of an entirely new one without much clarity on the specifics.

PIPELINES

Just two years ago, rapid production growth in the Permian Basin of Texas and New Mexico had overwhelmed regional infrastructure, causing bottlenecks that crushed local crude prices. Now, the region which is producing around four million barrels a day of oil has some three million barrels a day of excess pipeline space, according to East Daley Capital Advisors Inc., an energy data firm.

As we see from the chart above of continuous Midland/Brent spread futures, by 2018 production growth in the US Permian ahead of pipeline take-away capacity had driven Midland WTI to a discount of almost $25 to Brent crude oil before new pipelines were put in to operation. By mid-2019 stranded production in the Permian filled up new pipeline capacity and made it's way out of the region for export and the spread tightened to 2017 levels. Now that we've gone from bottlenecks in take-away capacity to the current 3 million barrels per day of unused capacity, that constraint of getting barrels to market has been removed.

REFINER UTILIZATION

Refineries work best when operating between 90-95%, and when running at 70-75% they often struggle to capture benchmark margins. We saw refining margins take a big hit earlier this year as a result of the end-use demand shock.

Gasoline and heating oil crack spreads to WTI for calendar 2021 and 2022 are shown on the left chart below.

However, outright prices, crack spreads and utilization rates have stabilized and traded sideways in a range since mid-2020.

With vaccines on the near horizon, the light at the end of the tunnel for the pandemic is no longer obfuscated. If you subscribe to a world view where there isn't a second wave of the Covid-19, maybe it's time to look at oil through a different lens by abandoning the bearish pandemic and embracing a more normal market structure.

EIA Inventory Statistics

Weekly Changes

The EIA reported a total petroleum inventory BUILD of 6.10_million barrels for the week ending November 27, 2020.

YTD Changes

Year-to-date, total inventory additions stand at a BUILD of 49.0 million barrels for the week ending November 27, 2020.

Inventory Levels

Commercial Inventory levels of Crude Oil (ex-SPR) Gasoline and Distillate are no longer in warning territory.

Lee Taylor - Technical Levels

(To return next week....)

Comments