The Chicken Or The Egg: Crude Oil Versus Refined Products

- bkkelly6

- May 16, 2021

- 7 min read

Author: Brynne Kelly 5/16/2021

The Colonial Pipeline (CPL), which delivers nearly half the transportation fuel to the Southeast and New York area, resumed full operations on Saturday, eight days after it was shut down by a ransomware attack. “We have returned the system to normal operations, delivering millions of gallons per hour to the markets we serve,” the operator of the pipeline said on Twitter. Even so, it will still take days for gas stations in the Southeast to restock after panic buying depleted their supplies.

The events surrounding the CPL outage were enough to stimulate oil prices higher. On a continual basis, the 3-year WTI futures strip has already rallied significantly this year. The strip even attempted to break the $60/bbl level early last week, only to pull back slightly by the end of the week and close at $59.67/bbl.

The last time the prompt 3-year average futures strip was above the $60 level was in 2018 and before that, 2015 (above, red circles).

The "Chicken-and-egg" question is a metaphoric adjective describing situations where it is not clear which of two events should be considered the cause and which should be considered the effect to express a scenario of infinite regress, or to express the difficulty of sequencing actions where each seems to depend on others being done first.

The global pandemic has highlighted and challenged this metaphor. U.S. and global oil demand through mid-February 2021 nearly returned to pre-COVID-19 levels, mainly due to strong refining and petrochemical needs as well as seasonal winter heating fuels demand. By all indications, global oil demand exceeded supply and supported prices since the third quarter of 2020. Current official global oil demand projections through 2022 call for record, two-year demand growth that could require virtually all of the world’s oil spare production capacity. Global oil drilling activity and capital investments have remained historically weak, suggesting a potential supply gap.

Cause and effect seemed quite obvious immediately following global lockdown orders last year. End-user demand was abruptly impaired causing refiners to reduce output, which reduced the amount of crude oil being processed and sent markets into a nosedive. What followed was a market structure that is extremely reactive to short-term fundamentals and an epic rally off of extreme lows.

Underneath the rally, noted above in strip prices, is a curve shape that has evolved into one of a very bullish nature. The shape of the curve moved from a contango structure at the beginning of 2019 (red line below) to backwardation by the start of 2020 (black line below). This backwardated structure has continued to stay in place as the entire curve shifted dramatically higher in 2021 (yellow line vs green line below).

At first glance, last Friday's curve settlement of outright prices far exceeds those seen not only at the beginning of this year, but also those from 2-years ago. However, a deeper comparison of the 1-month calendar spread curve structure (below) reveals that these calendar spreads have barely managed to return to 2020 levels (green line vs black line below). Essentially the spread curve as of last Friday's close shows that the level of backwardation currently expressed in the curve structure is similar to that of 2019 when outright prices were about $5 lower per barrel (green line vs black line).

A comparison of US crude oil inventory levels provides some context. Current US crude oil inventories (dark purple line below) are smack dab in the middle of 2015 and 2018 levels (both of which are years when the continuous 3-year strip moved above the $60/bbl level). For the inventory narrative to be supportive of current price levels, we would need to see US inventories continue to draw-down throughout the rest of the summer.

Beneath the simplicity of oil prices and inventory levels lies another level of nuance between markets that have the potential to make or break the complex. Another chicken and egg dilemma: Is it oil inventories, oil prices or refined product prices that are leading this market higher, or all three?

Gasoline Arb and RIN Prices

On the refined product side of the ledger is the arbitrage between European and US gasoline prices. As a result of the Colonial Pipeline outage, U.S. gasoline prices soared to multiyear seasonal highs. However, European gasoline prices have not rallied at a similar pace, opening up an arbitrage opportunity for European refiners. Refined products imports into the USAC increased to fill the supply shortage caused by the pipeline outage, with at least 9.56 million barrels, mostly gasoline, now expected to discharge in the week ended May 14 (data from ship tracking service Kpler shows, up from 8.24 million barrels the week prior). Refined products exports from the USGC increased to ease the supply surplus, with roughly 18 million barrels expected to be exported the week ended May 14, up from 13.7 million barrels the prior week, per the same Kpler data.

Like the continuous 3-year crude oil strip shown earlier, we see similar breaches of 2015 and 2018 highs in gasoline to those we saw in the crude oil strip. On a 12-month average basis, the UK to US-NYH gasoline futures spread in calendar 2022 is blowing out (pink line below). The U.S. East Coast accounts for nearly a third of the country’s total gasoline demand and this was put to the test with the CPL outage. European refiners produce more gasoline than required on that continent, and have long profited by exporting to the busy East Coast, as the price spread shows.

In the US, the marginal gallon of gasoline includes the cost of the RIN obligation, and any imported gallon of gasoline will also be saddled with the RIN obligation. That is why the melt-up in the spread has a lot to do with ethanol prices which are the primary driver of the US gasoline RIN obligation.

Prices for virtually all commodities began to climb in late 2020 and continued into 2021, and the price of RVOs (the Renewable Volume Obligation - RVO) rose alongside those increases. If there were no Renewable Fuel Standard in the U.S., there wouldn’t need to be an RVO value. But the standard does exist, so in some ways, the RVO is the last number tacked onto the chart, creating the final price of diesel and gasoline in the US.

According to the EIA, the front-month futures price of fuel ethanol closed higher than $2 per gallon on April 14 for the first time since Dec. 3, 2014. Fuel ethanol prices increased further throughout the remainder of April and settled at $2.34 on May 6, 23 cents per gallon higher than the front-month reformulated blendstock for oxygenate blending (RBOB) contract.

Again according to the EIA, RIN prices have increased sharply over recent months due to uncertainty concerning Renewable Fuel Standard blending requirements for 2021 and increased ethanol feedstock costs. This is evidenced in the next chart that incorporates continuous front month ethanol futures alongside US and European gasoline prices. The magnitude of the ethanol rally this year has been enough to pull US gasoline futures higher relative to import prices (red line below).

ULSD

A problem for the diesel market beyond the price of the RVO is the structure of the renewable fuels program: when the RVO gets high, it can incentivize making jet fuel instead of diesel. It can also incentivize exporting diesel rather than selling it into the domestic market. That is not new, it’s a permanent feature of the market. But as the price of RVOs increases, it increases those incentives. But the impact of higher RVO prices doesn’t end there. Compliance with the Renewable Fuel Standard is part of the U.S. transportation fuel supply, but it doesn’t govern exports. The economics of whether to put diesel into the domestic market, where the RVO would impact its price, or the export market, where it wouldn’t, could incentivize sending diesel abroad if that RVO value can’t be captured by the supplier.

The impact in the distillate market is the trade-off between jet fuel and diesel production. Both are distillates, and at the start of the pandemic, refiners tried to shift as much distillate output away from jet and toward diesel given the massive collapse in jet demand. That shift has eased and a more normal balance between jet and diesel output has returned. There is no renewable fuel standard for jet fuel, for a variety of reasons, including concern about fuel performance in jet engines. What that means is that the same calculation that goes into exporting diesel — the absence of an RVO hit — also is a factor in a refinery decision about whether to produce jet or diesel.

This dynamic is finally creating some tightness in ULSD calendar spreads. Typically in contango during the summer to entice summer storage of ULSD for winter usage, the front two summer spreads (June/July and July/August) moved to settle into backwardation last week (red arrow below).

This dynamic is finally offering a supportive element to front month WTI spreads which have been weak into expiration so far this year.

We need to see front month spreads hold their strength into expiration now that we are in the summer 'recovery' months in order for the flat price rally to continue.

Refined Product Relationships

Finally, we have the relationship between US gasoline and ULSD. To highlight this, we compare the prior and current Q4 inter-product spread. Gasoline futures have recovered quite a bit relative to ULSD prices this year (yellow line below). This rally could stall as jet fuel demand increases pulling molecules away from the distillate pool. Summer strength in ULSD prices is ultimately supportive crude oil prices.

What's apparent is that spread relationships are currently supportive of the oil price rally. We are in a deep chicken and egg feedback loop, and after the rally we have had this year all eyes are on which market can take the next lead.

_________________________________________________________________________________

EIA Inventory Statistics Recap

Weekly Changes

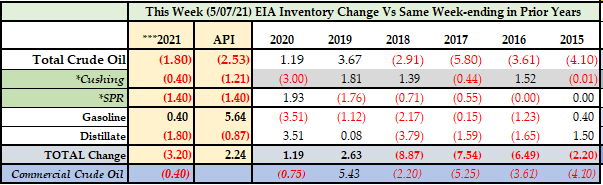

The EIA reported a total petroleum inventory DRAW of 3.20 million barrels for the week ending May 7, 2021 (vs a draw of 11.20 million barrels last week).

YTD Changes

Year-to-date cumulative changes in inventory for 2021 are DOWN by 35.70 million barrels (vs down 32.50 million last week).

Inventory Levels

Commercial Inventory levels of Crude Oil (ex-SPR) compared to prior years reflect progress that has been made in reducing excess inventory levels.

Comments